Host Elisa New explores Mark Doty’s meditation on love, the AIDS crisis, aging, and home with Doty, psychologist Steven Pinker, choreographer Bill T. Jones, fashion commentator Simon Doonan, and designer Jonathan Adler.

Interested in learning more? Poetry in America offers a wide range of courses, all dedicated to bringing poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

by Mark Doty

For years I went to the Peruvian barbers on 18th Street

—comforting, welcome: the full coatrack,

three chairs held by three barbers,

eldest by the window, the middle one

a slight fellow who spoke an oddly feminine Spanish,

the youngest last, red-haired, self-consciously masculine,

and in each of the mirrors their children’s photos,

mildly smutty cartoons, postcards from Machu Picchu.

I was happy in any chair, though I liked best

the touch of the oldest, who’d rest his hand

against my neck in a thoughtless, confident way.

Ten years maybe. One day the powdery blue

steel shutters pulled down over the window and door,

not to be raised again. They’d lost their lease;

I didn’t know how at a loss I’d feel—

this haze around what I’d like to think

the sculptural presence of my skull

requires neither art nor science,

but two haircuts on Seventh, one in Dublin,

nothing right.

Then (I hear my friend Marie

laughing over my shoulder, saying In your poems

there’s always a then, and I think, Is it a poem

without a then?) dull early winter, back on 18th,

upspiraling red in a cylinder of glass, and just below the line

of sidewalk, a new sign, WILLIE’S BARBERSHOP.

Dark hallway, glass door, and there’s (presumably)

Willie. When I tell him I used to go down the street

he says in an inscrutable accent, This your home now,

puts me in a chair, asks me what I want and soon he’s clipping

and singing with the radio’s Latin dance tune.

That’s when I notice Willie’s walls,

though he’s been here all of a week, spangled with images

hung in barbershops since the beginning of time:

lounge singers, near-celebrities, random boxers

—Italian boys, Puerto Rican, caught in the hour

of their beauty, though they’d scowl at the word—

victors cheering over a trophy won for what?

Frames already dusty, at slight angles,

here, it’s clear, forever. Are barbershops

like aspens, each sprung from a common root

ten thousand years old, sons of one father,

flashing fighters and starlets to shield the tenderness

at their hearts? Our guardian Willie defies time,

his chair our ferryboat, and we go down in the trance

of touch and the skull-buzz drone

singing cranial nerves in the direction of peace,

and so I understand that in the back

of this nothing building on 18th Street

—I’ve found that door ajar

before, in daylight, when it shouldn’t be,

some forgotten bulb left burning in a fathomless shaft

of my uncharted nights—

the men I have outlived

await their turns, the fevered and wasted, whose mothers

and lovers scattered their ashes and gave away their clothes.

Twenty years and their names tumble into a numb well

—though in truth I have not forgotten one of you,

may I never forget one of you—these layers of men,

arrayed in their no-longer breathing ranks.

Willie, I have not lived well in my grief for them;

I have lugged this weight from place to place

as though it were mine to account for,

and today I sit in your good chair, in the sixth decade

of my life, and if your back door is a threshold

of the kingdom of the lost, yours is a steady hand

on my shoulder. Go down into the still waters of this chair

and come up refreshed, ready to face the avenue.

Maybe I do believe we will not be left comfortless.

After everything comes tumbling down or you tear it down

and stumble in the shadow-valley trenches of the moon,

there’s still a decent chance at—a barbershop,

salsa on the radio, the instruments of renewal wielded,

effortlessly, and, who’d have thought, for you.

Willie if he is Willie fusses much longer over my head

than my head merits, which allows me to be grateful

without qualification. Could I be a little satisfied?

There’s a man who loves me. Our dogs. Fifteen,

twenty more good years, if I’m a bit careful.

There’s what I haven’t written. It’s sunny out,

though cold. After I tip Willie

I’m going down to Jane Street, to a coffee shop I like,

and then I’m going to write this poem. Then

For years I went to the Peruvian barbers on 18th Street

—comforting, welcome: the full coatrack,

three chairs held by three barbers,

eldest by the window, the middle one

a slight fellow who spoke an oddly feminine Spanish,

the youngest last, red-haired, self-consciously masculine,

and in each of the mirrors their children’s photos,

mildly smutty cartoons, postcards from Machu Picchu.

I was happy in any chair, though I liked best

the touch of the oldest, who’d rest his hand

against my neck in a thoughtless, confident way.

Ten years maybe. One day the powdery blue

steel shutters pulled down over the window and door,

not to be raised again. They’d lost their lease;

I didn’t know how at a loss I’d feel—

this haze around what I’d like to think

the sculptural presence of my skull

requires neither art nor science,

but two haircuts on Seventh, one in Dublin,

nothing right.

Then (I hear my friend Marie

laughing over my shoulder, saying In your poems

there’s always a then, and I think, Is it a poem

without a then?) dull early winter, back on 18th,

upspiraling red in a cylinder of glass, and just below the line

of sidewalk, a new sign, WILLIE’S BARBERSHOP.

Dark hallway, glass door, and there’s (presumably)

Willie. When I tell him I used to go down the street

he says in an inscrutable accent, This your home now,

puts me in a chair, asks me what I want and soon he’s clipping

and singing with the radio’s Latin dance tune.

That’s when I notice Willie’s walls,

though he’s been here all of a week, spangled with images

hung in barbershops since the beginning of time:

lounge singers, near-celebrities, random boxers

—Italian boys, Puerto Rican, caught in the hour

of their beauty, though they’d scowl at the word—

victors cheering over a trophy won for what?

Frames already dusty, at slight angles,

here, it’s clear, forever. Are barbershops

like aspens, each sprung from a common root

ten thousand years old, sons of one father,

flashing fighters and starlets to shield the tenderness

at their hearts? Our guardian Willie defies time,

his chair our ferryboat, and we go down in the trance

of touch and the skull-buzz drone

singing cranial nerves in the direction of peace,

and so I understand that in the back

of this nothing building on 18th Street

—I’ve found that door ajar

before, in daylight, when it shouldn’t be,

some forgotten bulb left burning in a fathomless shaft

of my uncharted nights—

the men I have outlived

await their turns, the fevered and wasted, whose mothers

and lovers scattered their ashes and gave away their clothes.

Twenty years and their names tumble into a numb well

—though in truth I have not forgotten one of you,

may I never forget one of you—these layers of men,

arrayed in their no-longer breathing ranks.

Willie, I have not lived well in my grief for them;

I have lugged this weight from place to place

as though it were mine to account for,

and today I sit in your good chair, in the sixth decade

of my life, and if your back door is a threshold

of the kingdom of the lost, yours is a steady hand

on my shoulder. Go down into the still waters of this chair

and come up refreshed, ready to face the avenue.

Maybe I do believe we will not be left comfortless.

After everything comes tumbling down or you tear it down

and stumble in the shadow-valley trenches of the moon,

there’s still a decent chance at—a barbershop,

salsa on the radio, the instruments of renewal wielded,

effortlessly, and, who’d have thought, for you.

Willie if he is Willie fusses much longer over my head

than my head merits, which allows me to be grateful

without qualification. Could I be a little satisfied?

There’s a man who loves me. Our dogs. Fifteen,

twenty more good years, if I’m a bit careful.

There’s what I haven’t written. It’s sunny out,

though cold. After I tip Willie

I’m going down to Jane Street, to a coffee shop I like,

and then I’m going to write this poem. Then

“This Your Home Now,” from DEEP LANE: POEMS by Mark Doty. Copyright © 2015 by Mark Doty. Used with permission by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

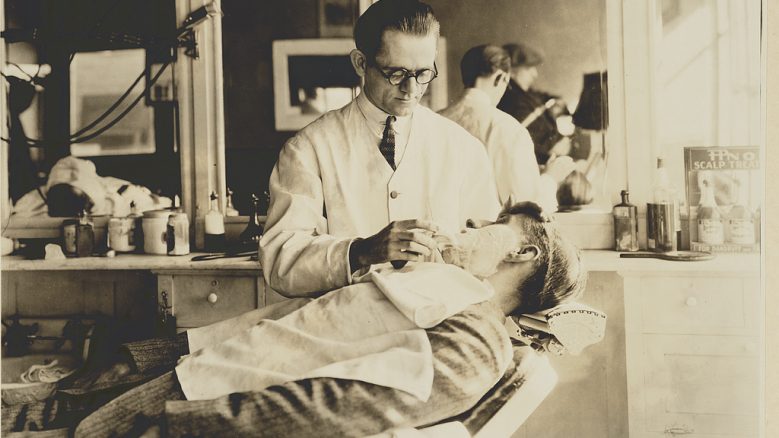

Mark Doty, in his poem “This Your Home Now,” reflects on the intimacy of sitting in the barber’s chair. “I was happy in any chair, though I liked best // the touch of the oldest, who’d rest his hand / against my neck in a thoughtless, confident way.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress

"We look at an experience and if we look hard enough, sometimes we can turn how we see it just a little bit. And in this case, it's looking at the loss of the barbershop, the loss, of course, of memory, of the loss of many people who are referenced in the poem." - Mark Doty

Barbershops come with an aesthetic and a history all their own. Photographs, memorabilia, and more fill the walls of the Malden Brothers Barber Shop in Montgomery, Alabama, where Martin Luther King, Jr., had his hair cut. Courtesy of the Carol M. Highsmith Archive/ Library of Congress

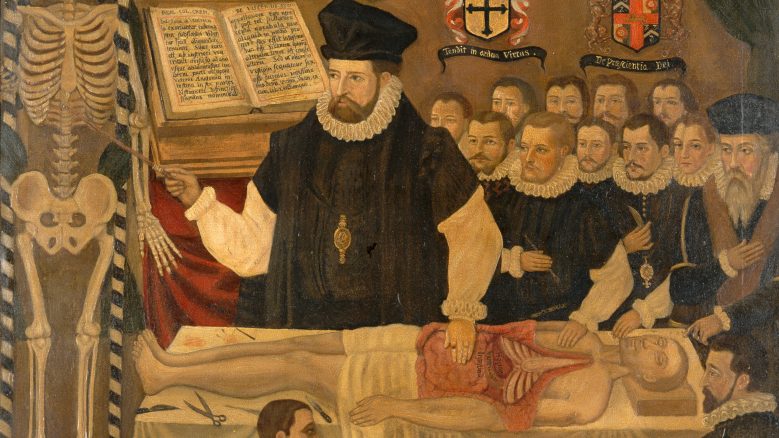

In medieval times, barbers weren’t responsible solely for the hair of their clients: they let blood, pulled teeth, and much more. Here, barber-surgeons in 16th-century London are being given an education in human anatomy. Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0.

"The poem is written in tercets, three line stanzas, and in a way that's a little bit of a nod to the great poem in tercets in the Western World, which is of course, the Divine Comedy, in which Dante is descending into hell." - Mark Doty

An AIDS memorial service in Provincetown on Cape Cod, commemorating those lost to the epidemic. Courtesy of The Provincetown Banner/GateHouse Media