Russian-born poet Joseph Brodsky wrote about the centaur as a Cold War self-portrait: a divided global refugee, created by a geopolitics of shifting borders and cultures. Theater of War productions artistic director Bryan Doerries, writer Yelena Akhtiorskaya, and scholars Sven Birkerts, Zakhar Ishov, Jonathan Brent, and Joseph Ellis read two poems by Brodsky: one about love; the other, exile.

Special thanks to our humanities advisers: Peter Kaufman, Claudia Sadowski-Smith, & Ramie Targoff.

Interested in learning more? Poetry in America offers a wide range of courses, all dedicated to bringing poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

SIX YEARS LATER

M.B.

So long had life together been that now

the second of January fell again

on Tuesday, making her astonished brow

lift like a windshield wiper in the rain,

so that her misty sadness cleared, and showed

a cloudless distance waiting up the road.

So long had life together been that once

the snow began to fall, it seemed unending;

that, lest the flakes should make her eyelids wince,

I’d shield them with my hand, and they, pretending

not to believe that cherishing of eyes,

would beat against my palm like butterflies.

So alien had all novelty become

that sleep’s entanglements would put to shame

whatever depths the analysts might plumb;

that when my lips blew out the candle flame,

her lips, fluttering from my shoulder, sought

to join my own, without another thought.

So long had life together been that all

that tattered brood of papered roses went,

and a whole birch grove grew upon the wall,

and we had money, by some accident,

and tonguelike on the sea, for thirty days,

the sunset threatened Turkey with its blaze.

So long had life together been without

books, chairs, utensils–only that ancient bed–

that the triangle, before it came about,

had been a perpendicular, the head

of some acquaintance hovering above

two points which had been coalesced by love.

So long had life together been that she

and I, with our joint shadows, had composed

a double door, a door which, even if we

were lost in work or sleep, was always closed:

somehow its halves were split and we went right

through them into the future, into night.

Epitaph for a Centaur

To say that he was unhappy is either to say too much

or too little: depending on who’s the audience.

Still, the smell he’d give off was a bit too odious,

and his canter was also quite hard to match.

He said, They meant just a monument, but something went astray:

the womb? the assembly line? the economy?

Or else, the war never happened, they befriended the enemy,

and he was left as it is, presumably to portray

Intransigence, Incompatibility–that sort of thing which proves

not so much one’s uniqueness or virtue, but probability.

For years, resembling a cloud, he wandered in olive groves,

marveling at one-leggedness, the mother of immobility.

Learned to lie to himself, and turned it into an art

for want of a better company, also to check his sanity.

And he died fairly young–because his animal part

turned out to be less durable than his humanity.

SIX YEARS LATER

M.B.

So long had life together been that now

the second of January fell again

on Tuesday, making her astonished brow

lift like a windshield wiper in the rain,

so that her misty sadness cleared, and showed

a cloudless distance waiting up the road.

So long had life together been that once

the snow began to fall, it seemed unending;

that, lest the flakes should make her eyelids wince,

I’d shield them with my hand, and they, pretending

not to believe that cherishing of eyes,

would beat against my palm like butterflies.

So alien had all novelty become

that sleep’s entanglements would put to shame

whatever depths the analysts might plumb;

that when my lips blew out the candle flame,

her lips, fluttering from my shoulder, sought

to join my own, without another thought.

So long had life together been that all

that tattered brood of papered roses went,

and a whole birch grove grew upon the wall,

and we had money, by some accident,

and tonguelike on the sea, for thirty days,

the sunset threatened Turkey with its blaze.

So long had life together been without

books, chairs, utensils–only that ancient bed–

that the triangle, before it came about,

had been a perpendicular, the head

of some acquaintance hovering above

two points which had been coalesced by love.

So long had life together been that she

and I, with our joint shadows, had composed

a double door, a door which, even if we

were lost in work or sleep, was always closed:

somehow its halves were split and we went right

through them into the future, into night.

Epitaph for a Centaur

To say that he was unhappy is either to say too much

or too little: depending on who’s the audience.

Still, the smell he’d give off was a bit too odious,

and his canter was also quite hard to match.

He said, They meant just a monument, but something went astray:

the womb? the assembly line? the economy?

Or else, the war never happened, they befriended the enemy,

and he was left as it is, presumably to portray

Intransigence, Incompatibility–that sort of thing which proves

not so much one’s uniqueness or virtue, but probability.

For years, resembling a cloud, he wandered in olive groves,

marveling at one-leggedness, the mother of immobility.

Learned to lie to himself, and turned it into an art

for want of a better company, also to check his sanity.

And he died fairly young–because his animal part

turned out to be less durable than his humanity.

“Six Years Later” translated by Richard Wilbur from SELECTED POEMS 1968-1996 edited by Ann Kjellberg with translations from the Russian by several translators. Copyright © 2020 by the Estate of Joseph Brodsky. Selection copyright © 2020 by The Joseph Brodsky Article Fourth Trust. “Epitaph for a Centaur” from SO FORTH by Joseph Brodsky. Copyright © 1996 by Estate of Joseph Brodsky.

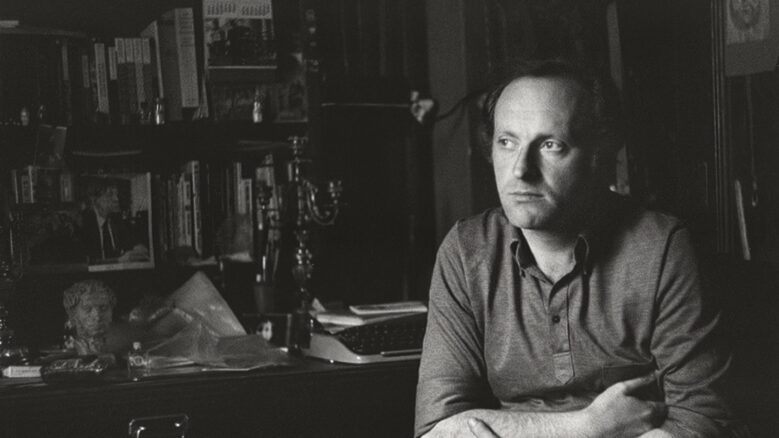

Arguably the most famous post-War Russian poet, Joseph Brodsky was championed in his own country by established poets like Anna Akhamatova and popular in more rebellious intellectual circles, spreading through covert samizdat publications. This brought him some unwanted government attention. Image credit: Photo Brodsky "Last day at the apartment" © Lev Poliakov

In “Six Years Later” Brodsky compares the falling of snow to the beating wings of butterflies. (The falling snow, in turn, he compared to the unending avalanche of love.) Multi-media artist Wendy Ultan made this and several other paintings to help us capture Brodsky’s more expressionistic material.

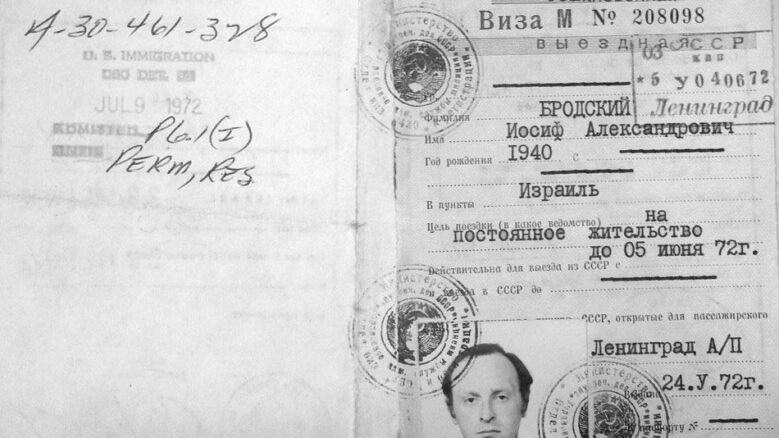

In 1963, Brodsky’s poetry was denounced as “Anti-Soviet and Pornographic.” He was expelled from Leningrad and sentenced to five years of "internal exile in the North at hard labor" and settled in Norenskaya. After eighteen months, his high profile and the efforts of his friends (including Anna Akhmatova, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Dmitri Shostakovich) got his sentence commuted. Image courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

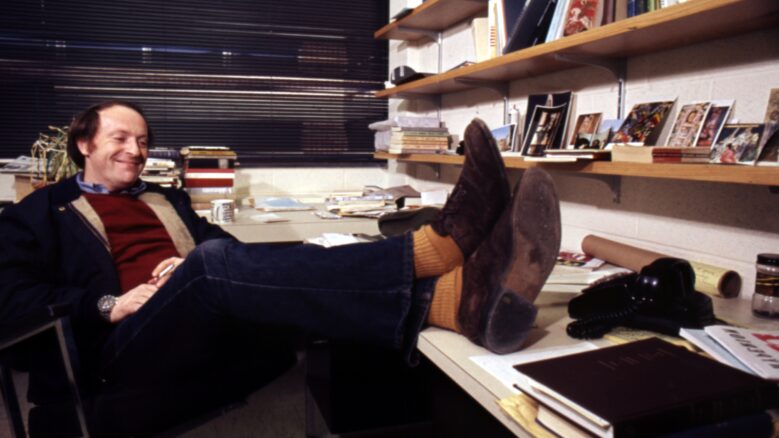

By the early 1970s Brodsky had become persona non grata in Russia and, in 1972, his apartment was broken into and he was put on a plane to Vienna. While in Austria he met Carl Proffer, a Professor of Russian at the University of Michigan, who facilitated Brodsky’s emigration to the US and his hiring at the University.

Although Brodsky would teach at a variety of Universities in the West—including Smith, Columbia, and Cambridge—he spent the longest time at Michigan. Brodsky was popular with students and enjoyed the vocation. Some of his pedagogical tools, like his reading list, have become classics. Image credit: Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

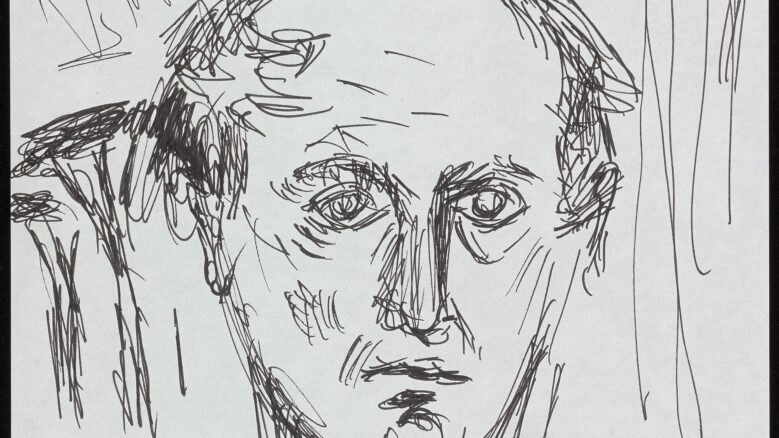

In the margins of his essays and poems, Brodsky would often doodle and sketch. Brodsky was a talented artist, and we were privileged to get access from the Bienecke Library at Yale and the Hoover Library at Stanford to a wide variety of Brodsky’s pencilwork. Above we have a Self-Portrait, courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

What if a global conflict literally divided you? Exiled to the U.S. during the Cold War, Russian-born poet Joseph Brodsky identified with the centaur, a figure from Greek mythology that is half man, half horse. The drawing, by Brodsky, is courtesy of Ann Kjellberg.