Do good fences really make good neighbors? Robert Frost’s “Mending Wall” asks surprising questions about the role of walls in civil society. Host Elisa New gathers Ambassador Caroline Kennedy, author Julia Alvarez, political commentator David Gergen, Frost biographer and poet Jay Parini, poet Rhina Espaillat, and former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith to delve into this classic poem.

Special thanks to our humanities adviser: Robert Pinsky.

Interested in learning more? Poetry in America offers a wide range of courses, all dedicated to bringing poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

by Robert Frost

Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of outdoor game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44266/mending-wall

Mending Wall

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun;

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing:

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made,

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go.

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

‘Stay where you are until our backs are turned!’

We wear our fingers rough with handling them.

Oh, just another kind of outdoor game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

‘Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That wants it down.’ I could say ‘Elves’ to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed.

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44266/mending-wall

Poet and novelist Jay Parini traces the themes of Frost's "Mending Wall"—in particular, the ritualistic building of boundaries—all the way back to ancient Rome: "It goes back to the old festival of Terminalia. Terminus was the Roman God of boundaries, and once a year in the early spring, the Romans would gather and mend fences."' Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

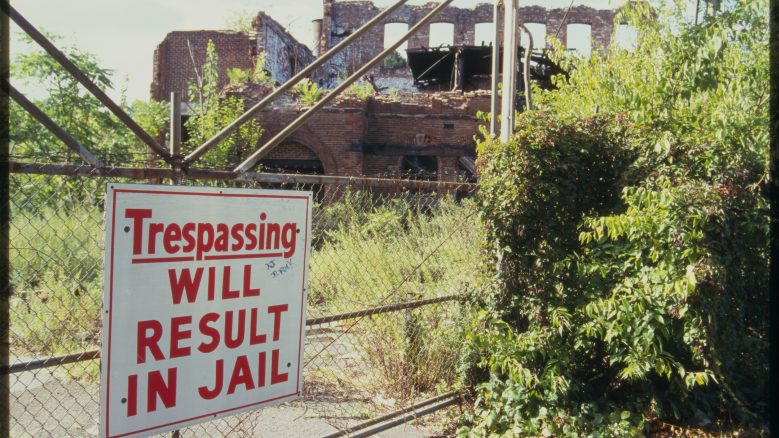

The geopolitical history of the twentieth century is a history of boundaries, of the erection of walls and their tearing down. Frost's "Mending Wall" challenges the way we understand the relationship between civilization and wall-building, and asks us to reflect on the ways, and the reasons, we put walls up or take them down. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Frost's poem remains keenly relevant today. Novelist Julia Alvarez considers the poem in context of the US's southern border: "You know, as a Latina now, I have a new reaction to this poem, saying, yeah, you know, before you build a wall ask first, you know what you're walling in or walling out, and to whom you're like to give offense." Courtesy of U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Robert Frost first published "Mending Wall" in 1914, as a part of his collection North of Boston. The collection treated themes of life in rural New England, where Frost for much of his would live, and the poem "Mending Wall" in particular is informed by the traditions and rituals of farm living. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives Collections.

"There's a very old-fashioned notion that goes way back early in American history, property being so important. John Locke, who was so important to the Founders, wrote about life, liberty and property. That was the role of the state. It wasn't life, liberty and happiness. It was life, liberty and property" - Political commentator David Gergen. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Poet Rhina Espaillat, born in the Dominican Republic, considers Frost's themes of conflict and division in the context of political despotism. "The only way to avoid arguments in a society is by having a dictatorship. Now, the country that I was born in was a dictatorship that lasted 30 years and we had no arguments at all for those 30 years. Because he did what he pleased."

Former US Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy reflects on the power of art within politics, and the importance of art to her father, John F. Kennedy: "Robert Frost went and read this poem in Russia. It was the time of the Berlin Wall and all of that. And then, I think my father gave one of his great speeches at the Robert Frost Library dedication at Amherst, where he talked about the role of the artist is to question authority, and to question power."

For poet Tracy K. Smith, Frost's poem engages pressing questions of belonging and identity: "If you are not native to a place, native folkways are something that bar you from really full integration. There's a part of this poem that I believe is about eliminating different barriers to belonging."