Celebrate Walt Whitman’s 200th birthday with Justice Elena Kagan, playwright Tony Kushner, music legend Nas, composer Matthew Aucoin, baritone Davóne Tines, poets Joshua Bennett, Marilyn Chin, Linda Hogan, and Adrienne Raphel, Mark Doty, and more!

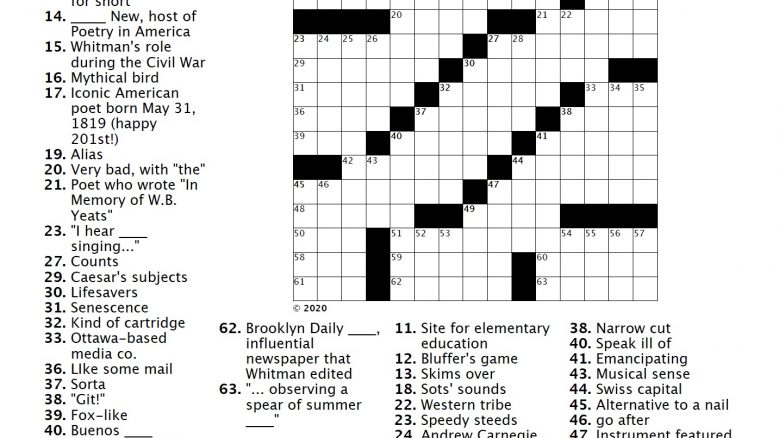

Want to test your Whitman knowledge? Episode guest, poet, and cruciverbalist Adrienne Raphel has made a special Whitman-focused crossword to celebrate the poet’s 200th birthday.

Try it here:

https://www.poetryinamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/whitman_puzzle_raphel.pdf

Solution is here:

https://www.poetryinamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SOLUTION_whitman.pdf

Interested in learning more? Poetry in America offers a wide range of courses, all dedicated to bringing poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

by Walt Whitman

The pure contralto sings in the organloft,

The carpenter dresses his plank . . . . the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild ascending lisp,

The married and unmarried children ride home to their thanksgiving dinner,

The pilot seizes the king-pin, he heaves down with a strong arm,

The mate stands braced in the whaleboat, lance and harpoon are ready,

The duck-shooter walks by silent and cautious stretches,

The deacons are ordained with crossed hands at the altar,

The spinning-girl retreats and advances to the hum of the big wheel,

The farmer stops by the bars of a Sunday and looks at the oats and rye,

The lunatic is carried at last to the asylum a confirmed case,

He will never sleep any more as he did in the cot in his mother’s bedroom;

The jour printer with gray head and gaunt jaws works at his case,

He turns his quid of tobacco, his eyes get blurred with the manuscript;

The malformed limbs are tied to the anatomist’s table,

What is removed drops horribly in a pail;

The quadroon girl is sold at the stand . . . . the drunkard nods by the barroom stove,

The machinist rolls up his sleeves . . . . the policeman travels his beat . . . . the gate-keeper marks who pass,

The young fellow drives the express-wagon . . . . I love him though I do not know him;

The half-breed straps on his light boots to compete in the race,

The western turkey-shooting draws old and young . . . . some lean on their rifles, some sit on logs,

Out from the crowd steps the marksman and takes his position and levels his piece;

The groups of newly-come immigrants cover the wharf or levee,

The woollypates hoe in the sugarfield, the overseer views them from his saddle;

The bugle calls in the ballroom, the gentlemen run for their partners, the dancers bow to each other;

The youth lies awake in the cedar-roofed garret and harks to the musical rain,

The Wolverine sets traps on the creek that helps fill the Huron,

The reformer ascends the platform, he spouts with his mouth and nose,

The company returns from its excursion, the darkey brings up the rear and bears the well-riddled target,

The squaw wrapt in her yellow-hemmed cloth is offering moccasins and beadbags for sale,

The connoisseur peers along the exhibition-gallery with halfshut eyes bent sideways,

The deckhands make fast the steamboat, the plank is thrown for the shoregoing passengers,

The young sister holds out the skein, the elder sister winds it off in a ball and stops now and then for the knots,

The one-year wife is recovering and happy, a week ago she bore her first child,

The cleanhaired Yankee girl works with her sewing-machine or in the factory or mill,

The nine months’ gone is in the parturition chamber, her faintness and pains are advancing;

The pavingman leans on his twohanded rammer—the reporter’s lead flies swiftly over the notebook—the signpainter is lettering with red and gold,

The canal-boy trots on the towpath—the bookkeeper counts at his desk—the shoemaker waxes his thread,

The conductor beats time for the band and all the performers follow him,

The child is baptised—the convert is making the first professions,

The regatta is spread on the bay . . . . how the white sails sparkle!

The drover watches his drove, he sings out to them that would stray,

The pedlar sweats with his pack on his back—the purchaser higgles about the odd cent,

The camera and plate are prepared, the lady must sit for her daguerreotype,

The bride unrumples her white dress, the minutehand of the clock moves slowly,

The opium eater reclines with rigid head and just-opened lips,

The prostitute draggles her shawl, her bonnet bobs on her tipsy and pimpled neck,

The crowd laugh at her blackguard oaths, the men jeer and wink to each other,

(Miserable! I do not laugh at your oaths nor jeer you,)

The President holds a cabinet council, he is surrounded by the great secretaries,

On the piazza walk five friendly matrons with twined arms;

The crew of the fish-smack pack repeated layers of halibut in the hold,

The Missourian crosses the plains toting his wares and his cattle,

The fare-collector goes through the train—he gives notice by the jingling of loose change,

The floormen are laying the floor—the tinners are tinning the roof—the masons are calling for mortar,

In single file each shouldering his hod pass onward the laborers;

Seasons pursuing each other the indescribable crowd is gathered . . . . it is the Fourth of July . . . . what salutes of cannon and small arms!

Seasons pursuing each other the plougher ploughs and the mower mows and the wintergrain falls in the ground;

Off on the lakes the pikefisher watches and waits by the hole in the frozen surface,

The stumps stand thick round the clearing, the squatter strikes deep with his axe,

The flatboatmen make fast toward dusk near the cottonwood or pekantrees,

The coon-seekers go now through the regions of the Red river, or through those drained by the Tennessee, or through those of the Arkansas,

The torches shine in the dark that hangs on the Chattahoochee or Altamahaw;

Patriarchs sit at supper with sons and grandsons and great grandsons around them,

In walls of abode, in canvass tents, rest hunters and trappers after their day’s sport.

The city sleeps and the country sleeps,

The living sleep for their time . . . . the dead sleep for their time,

The old husband sleeps by his wife and the young husband sleeps by his wife;

And these one and all tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them,

And such as it is to be of these more or less I am.

The pure contralto sings in the organloft,

The carpenter dresses his plank . . . . the tongue of his foreplane whistles its wild ascending lisp,

The married and unmarried children ride home to their thanksgiving dinner,

The pilot seizes the king-pin, he heaves down with a strong arm,

The mate stands braced in the whaleboat, lance and harpoon are ready,

The duck-shooter walks by silent and cautious stretches,

The deacons are ordained with crossed hands at the altar,

The spinning-girl retreats and advances to the hum of the big wheel,

The farmer stops by the bars of a Sunday and looks at the oats and rye,

The lunatic is carried at last to the asylum a confirmed case,

He will never sleep any more as he did in the cot in his mother’s bedroom;

The jour printer with gray head and gaunt jaws works at his case,

He turns his quid of tobacco, his eyes get blurred with the manuscript;

The malformed limbs are tied to the anatomist’s table,

What is removed drops horribly in a pail;

The quadroon girl is sold at the stand . . . . the drunkard nods by the barroom stove,

The machinist rolls up his sleeves . . . . the policeman travels his beat . . . . the gate-keeper marks who pass,

The young fellow drives the express-wagon . . . . I love him though I do not know him;

The half-breed straps on his light boots to compete in the race,

The western turkey-shooting draws old and young . . . . some lean on their rifles, some sit on logs,

Out from the crowd steps the marksman and takes his position and levels his piece;

The groups of newly-come immigrants cover the wharf or levee,

The woollypates hoe in the sugarfield, the overseer views them from his saddle;

The bugle calls in the ballroom, the gentlemen run for their partners, the dancers bow to each other;

The youth lies awake in the cedar-roofed garret and harks to the musical rain,

The Wolverine sets traps on the creek that helps fill the Huron,

The reformer ascends the platform, he spouts with his mouth and nose,

The company returns from its excursion, the darkey brings up the rear and bears the well-riddled target,

The squaw wrapt in her yellow-hemmed cloth is offering moccasins and beadbags for sale,

The connoisseur peers along the exhibition-gallery with halfshut eyes bent sideways,

The deckhands make fast the steamboat, the plank is thrown for the shoregoing passengers,

The young sister holds out the skein, the elder sister winds it off in a ball and stops now and then for the knots,

The one-year wife is recovering and happy, a week ago she bore her first child,

The cleanhaired Yankee girl works with her sewing-machine or in the factory or mill,

The nine months’ gone is in the parturition chamber, her faintness and pains are advancing;

The pavingman leans on his twohanded rammer—the reporter’s lead flies swiftly over the notebook—the signpainter is lettering with red and gold,

The canal-boy trots on the towpath—the bookkeeper counts at his desk—the shoemaker waxes his thread,

The conductor beats time for the band and all the performers follow him,

The child is baptised—the convert is making the first professions,

The regatta is spread on the bay . . . . how the white sails sparkle!

The drover watches his drove, he sings out to them that would stray,

The pedlar sweats with his pack on his back—the purchaser higgles about the odd cent,

The camera and plate are prepared, the lady must sit for her daguerreotype,

The bride unrumples her white dress, the minutehand of the clock moves slowly,

The opium eater reclines with rigid head and just-opened lips,

The prostitute draggles her shawl, her bonnet bobs on her tipsy and pimpled neck,

The crowd laugh at her blackguard oaths, the men jeer and wink to each other,

(Miserable! I do not laugh at your oaths nor jeer you,)

The President holds a cabinet council, he is surrounded by the great secretaries,

On the piazza walk five friendly matrons with twined arms;

The crew of the fish-smack pack repeated layers of halibut in the hold,

The Missourian crosses the plains toting his wares and his cattle,

The fare-collector goes through the train—he gives notice by the jingling of loose change,

The floormen are laying the floor—the tinners are tinning the roof—the masons are calling for mortar,

In single file each shouldering his hod pass onward the laborers;

Seasons pursuing each other the indescribable crowd is gathered . . . . it is the Fourth of July . . . . what salutes of cannon and small arms!

Seasons pursuing each other the plougher ploughs and the mower mows and the wintergrain falls in the ground;

Off on the lakes the pikefisher watches and waits by the hole in the frozen surface,

The stumps stand thick round the clearing, the squatter strikes deep with his axe,

The flatboatmen make fast toward dusk near the cottonwood or pekantrees,

The coon-seekers go now through the regions of the Red river, or through those drained by the Tennessee, or through those of the Arkansas,

The torches shine in the dark that hangs on the Chattahoochee or Altamahaw;

Patriarchs sit at supper with sons and grandsons and great grandsons around them,

In walls of abode, in canvass tents, rest hunters and trappers after their day’s sport.

The city sleeps and the country sleeps,

The living sleep for their time . . . . the dead sleep for their time,

The old husband sleeps by his wife and the young husband sleeps by his wife;

And these one and all tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them,

And such as it is to be of these more or less I am.

“Leaves of Grass” by Walt Whitman (1855)

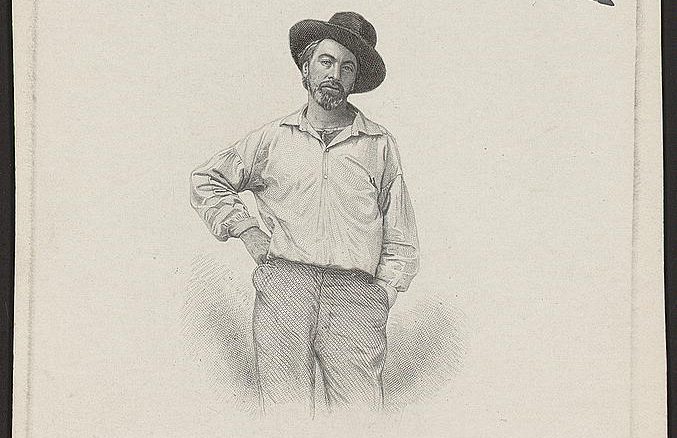

Walt Whitman is hailed as one of the most significant American poets of all time. Born in 1819, he grew up in Brooklyn where he witnessed a New York caught up in the throes of modernity: his poetry, in its metrical and rhythmic innovation, is a testament to this evolving American spirit. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

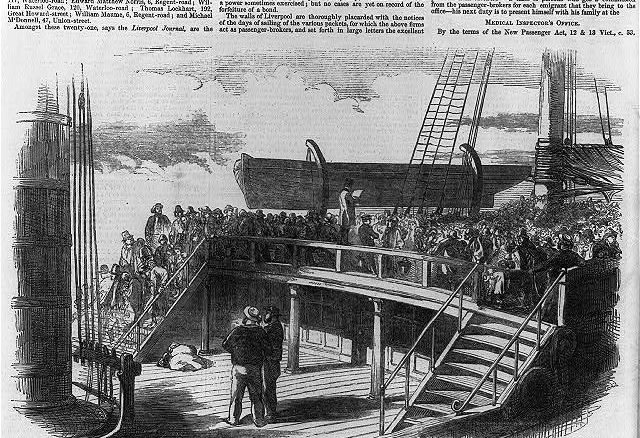

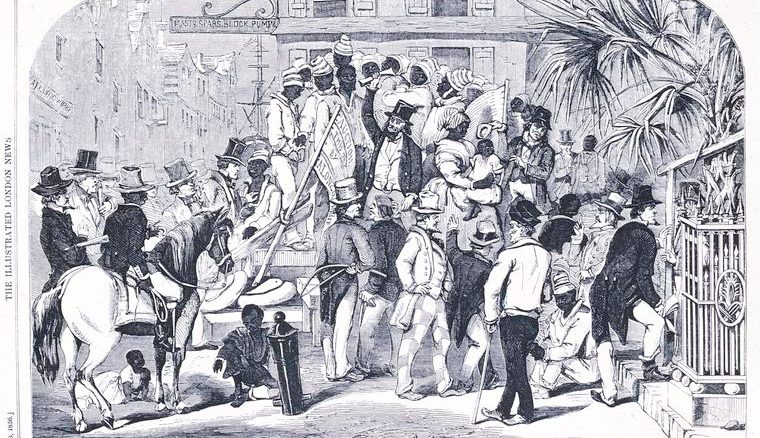

America in the 19th century saw its population grow spectacularly, as immigrants flocked to the newly-made United States from all over the world—and many of these immigrants entered their new home through Whitman’s New York. Playwright Tony Kushner considers Whitman’s place among these new and different voices: “His job as a poet is to make himself open to this continent of dissonant voices.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress

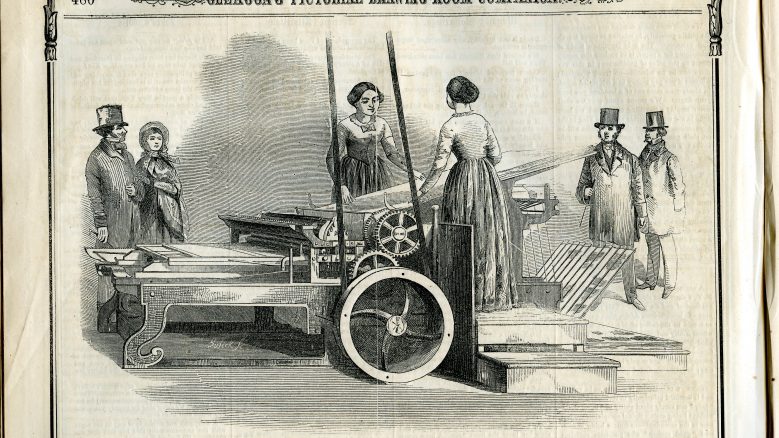

At the age of 12, Walt Whitman apprenticed to a Brooklyn printer. 24 years later, Whitman self-published the first 1855 edition of his landmark collection of poems “Leaves of Grass”—setting the type and working the press himself. Courtesy of the collection of Elisa New

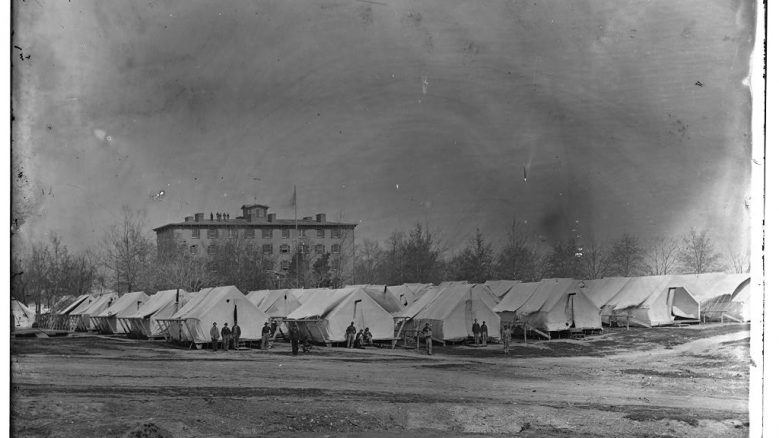

Soon after the 1855 publication of the first edition of his “Leaves of Grass,” the American Civil War broke out. This conflict was not only to change the social and political landscape of the United States, but also Whitman’s own poetic sensibilities as he witnessed the battlefields of Virginia and the hospital wards of Washington, D.C. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In “Leaves of Grass,” Whitman juxtaposes a number of very different images: in one line he imagines a slave working in Southern sugar-fields, and in the next a gentleman at a high-society ball. Poet Joshua Bennett considers the contradictions in American life that Whitman pointed to in his poetry: “The labor and the violence of the sugar field makes what's happening in the ballroom possible. And it brings to mind that famous line from Emerson, that there's blood in the sugar, there's blood in the tea, blood in the coffee, right?” Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Episode guest, acclaimed poet, and cruciverbalist Adrienne Raphel has made a special Whitman crossword for Poetry in America! Access the puzzle here: https://www.poetryinamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/whitman_puzzle_raphel.pdf