An Experiment in Blended Learning: Bringing Poetry in America for Teachers into My Classroom

by Khriseten Bellows

This post was written by Khriseten Bellows, who led a group of high-school students in a blended-learning version of the Poetry in America for Teachers: The City from Whitman to Hip Hop online course in the Spring of 2017. Khriseten is a National Board Certified teacher with 24 years of teaching experience. Currently based in San Diego, she serves as an instructional coach for teachers.

The San Diego Teaching Experiment

The Jacarandas are in bloom. They stretch elegant fingers around the bus stops, the laundromat’s weathered façade, Filiberto’s Taco Shop, eclipsing the view of Route 15 with an explosion of tiny, desperately purple flowers.

Photo Credit: JACARANDA by Sharin

Last spring was my first in San Diego, and it seemed that, one night, the barren Jacarandas pooled their folded leaves and delicate buds, and, by morning, had exploded into rows of vivid purple orbs. The effect overwhelmed me as I drove down University Avenue. All I could say to myself was: What is their name? What are they called?

Photo Credit: JACARANDAS by hollywoodsmille310

As I pulled up to Health Sciences High and Middle College, some of my students were milling around in small groups, nudging each other, smiling, laughing, snapping photos. “Hey, you guys,” I asked them, “do you know what those trees are called?” Shouting all at once, they exclaimed “Jacarandas!” “ Jakarandah” “Jakayrada” “Jaka landa”! Whether they were from Somalia, Mexico, Kenya, Hawaii, Korea, America, or Japan, it was the same sounding word.

And it is with this notion of unity through language, that I approach my work as “on-site instructor” with these students.

A World Within A Classroom

Having taught in a traditional classroom setting for twenty-four years, my purpose now was to create a face-to-face course, for two hours, once a week, while using Poetry In America’s online content. Although most of the course’s submissions–the discussions, responses, and essays–are completed online, I wanted to design a class with the intent to analyze the course material at a deeper, more interactive level.

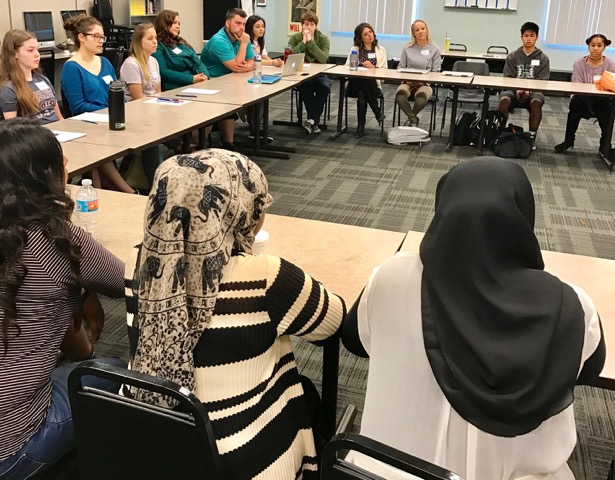

Khriseten Bellows’s high-school students discuss a poem during their Poetry in America class

After a flurry of registration forms and over 15 more students than I had expected, we catapulted in. At first, we experimented with Canvas’ annotation tools, but very quickly found the ‘old fashion’ way: pen to paper, a more immediate, more tangible way of looking at the work. With a gradual-release technique, I modeled how to ‘enter’ a poem: What questions to ask, which aspects to be aware of during the initial and subsequent reads. As a ritual to begin each class, we find our seats in a circle, and I ask someone to read the poem aloud. And once the poem has been read, the students turn to each other with questions.

Every Thursday at 9:30am, I get to hear their interpretations—their free-flowing thoughts—about each of the poems on the syllabus. Max, a shaggy haired, charismatic senior observed last week that, “Every time we meet, I am shown a new way to look at a poem. Having a group around you with multiple perspectives—it’s knowledge that can totally change the way you interpret. Like our discussion about [Todd Colby’s] “Wednesday Poem”, I feel like we just dove in and went crazy analyzing! But, we could have gone in a different direction completely, and it would have felt just as valid! That’s what I love about our class!” Keller, his love, who is also in the course, chimed in, “I had a poetry class in 7th Grade, and I didn’t like reading poems at all. I felt so embarrassed that I actually couldn’t speak in public. But, here, it is so comfortable to take risks, and to learn from my classmates and you. I cannot get that online.”

At 12:35pm every Thursday, the juniors spend the lunch hour as class time. They tumble in complaining about College Stats, the stress of this year, and the freshmen who block the halls with their double-stuffed backpacks. This was the group I adopted last year when their previous teacher had to take a leave of absence. Having two weeks of substitutes, the student teachers gave up, and these sophomores made a collective decision: “We all agreed to make it miserable for you, so bad that you would leave like everyone else has since we were in 7th Grade!” After those challenging months, and slow, deepening affection for each other over the following school year, they signed up for the course with me. I had endured their resistance to change and reassured them that giving up was not an option. Jacaranda. They did have a common language. It was betrayal then. But it was togetherness now.

Everyone in our group is from a unique corner of the world. Hamdi, Ikran, Asha, Rabab, and Manira are Somali; Lilly is Korean, and a Non-Denominational Christian. Justin and Alyssa are Filipino, and Myka is Japanese and an atheist. Ishaan is Indian, and Janalyn comes from Mississippi. Alyza comes from California, and Carel from Mexico.

Collaborative Learning

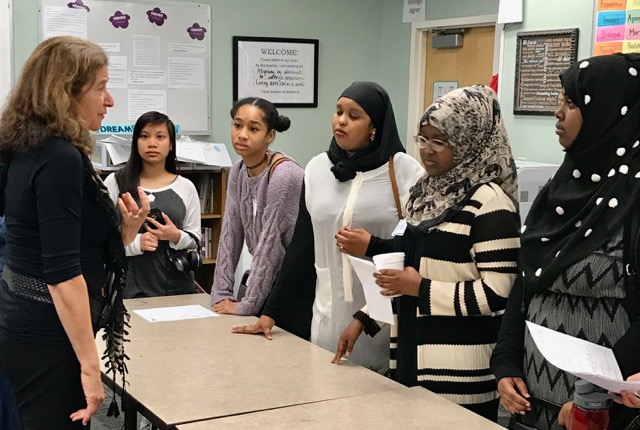

Professor New visits students in Khriseten’s Poetry in America class

Having such a compelling subject to share creates new ways of relating. Halfway through the semester, we sat around after class discussing how cool it is that everyone approaches the poems with his or her “own life in the forefront.” Through the haze of electronics and frenetic friendships, I realized that the texts were helping them articulate and empathize with another human’s experience, and in every piece, they could find a universal connection. “Just in the last couple months, we got so much closer while finding a deeper understanding from each other,” said Alyza. “That’s what kicked-started us every time.” “Yeah.” Lilly chimed in, “Now, I feel like I comprehend poetry on a level where I can have long conversations and debates about poems! And to have a teacher that supports me throughout the course also helped identify concrete evidence and reasoning behind my understanding. You really push us by asking good questions, challenging our thoughts, wondering all the while.” That is what happens when students are invested, intrigued, and allowed to be collaborative. It is an organic process that stretches their limbs towards the sky.

Everyone Is Welcome

It is this element of the course—the excitement and interest and excavation—that propels me out into the sun at the end of each day. I know teenagers. They are teeming with impulsive ideas. They are funny, dizzying, mercurial. They are best part of the job. Each week, we print up the unit poems, decide which ones to annotate together, and dive in. [Watch Khriseten’s students in action HERE.] Sometimes friends of my students, who have a free period, will join in. One morning, a guy named Shimari was looming around the table waiting for the seniors and Calculus to start. So, I welcomed him to join us. I had no idea how comfortable he would be, but he ended up leading the discussion. Afterwards, I wondered how he felt about the experience: “It makes me want to be in the class and just be in this small group,” he enthusiastically replied. “It represents openness, and usually I don’t like reading. But this felt great!” He went on to email me later to ask my opinion about which college courses to take to double major in Business and English.

Khriseten’s students annotate and discuss a poem during class

Yassar, a senior, is always hanging around, waiting for our group to finish up, which is the reason I ‘hired’ him to film our round-table discussion. “This is such a sophisticated and intelligent group!” he said at the end of yesterday’s session, “ I would love to join if I could.” As the students bond over the texts, a natural curiosity germinates throughout the school prompting other students to ask when they can take the class.

Face-To-Face Learning

Even though there is burgeoning interest in the course, students need to write analytical essays, which requires well-honed skills. Many of them are hesitant and lack confidence. But, luckily, I love teaching writing because it requires intense scrutiny and ruthless editing, a focused rigor that most students don’t enjoy. That’s another reason why teaching jazzes me—my goal is always to make the work less arduous, less frustrating, and more enjoyable. Every day that I teach, the wise words of my 8th Grade teacher, Mrs. Randolph, cackle in my ear: “It [revising] puts starch in your shirt!”

And I, too, subscribe to that adage.

Khriseten helps a student revise an essay during a workshopping session

Therefore, twice this semester, I offered one-on-one conferences for rewriting essays. Surprisingly, from the outset, almost everyone showed up, rolling in after four, 90-minute classes—an intense day at HSHMC. Even so, poring over their words with them allowed me to help sharpen their writing skills, lead them through revisions and editing, and laugh at their endearing humor. In these meetings, I aim to help guide, organize, and craft their critical writing, which ultimately translates into greater confidence working in groups, a more informed collaboration with peers, and a “a higher standard of learning.” [Watch Khriseten’s students discuss the writing process HERE.]

The Power of Poetry: The Final Project

Today, as the purple haze of Jacarandas hums over our streets, my poetry students are creating their final projects, writing lesson plans, deciding who will tackle the various elements of a selected poem from the course: structure, language, historical background. By May 14th, they will have designed, taught, and videotaped an original lesson to teenagers just a bit younger than themselves. That is the final test of their mastery. As we wind down our school year, the notion of home feels imbued in the trees lining our sun-drenched city, and the words that we share. And now, at the end of this intense semester of genuine connection and poetry analysis, we have identified a word to articulate this cultivated bond between us—family.