In this environmental science episode, Vice President Al Gore, poet Jorie Graham, and scientists from Conservation International dive into Moore’s portrayal of the always-changing ocean, and its future in a warming world.

Interested in learning more? Poetry in America offers a wide range of courses, all dedicated to bringing poetry into classrooms and living rooms around the world.

by Marianne Moore

wade

through black jade.

Of the crow-blue mussel-shells, one keeps

adjusting the ash-heaps;

opening and shutting itself like

an

injured fan.

The barnacles which encrust the side

of the wave, cannot hide

there for the submerged shafts of the

sun,

split like spun

glass, move themselves with spotlight swiftness

into the crevices—

in and out, illuminating

the

turquoise sea

of bodies. The water drives a wedge

of iron through the iron edge

of the cliff; whereupon the stars,

pink

rice-grains, ink-

bespattered jelly-fish, crabs like green

lilies, and submarine

toadstools, slide each on the other.

All

external

marks of abuse are present on this

defiant edifice—

all the physical features of

ac-

cident—lack

of cornice, dynamite grooves, burns, and

hatchet strokes, these things stand

out on it; the chasm side is

dead.

Repeated

evidence has proved that it can live

on what can not revive

its youth. The sea grows old in it.

wade

through black jade.

Of the crow-blue mussel-shells, one keeps

adjusting the ash-heaps;

opening and shutting itself like

an

injured fan.

The barnacles which encrust the side

of the wave, cannot hide

there for the submerged shafts of the

sun,

split like spun

glass, move themselves with spotlight swiftness

into the crevices—

in and out, illuminating

the

turquoise sea

of bodies. The water drives a wedge

of iron through the iron edge

of the cliff; whereupon the stars,

pink

rice-grains, ink-

bespattered jelly-fish, crabs like green

lilies, and submarine

toadstools, slide each on the other.

All

external

marks of abuse are present on this

defiant edifice—

all the physical features of

ac-

cident—lack

of cornice, dynamite grooves, burns, and

hatchet strokes, these things stand

out on it; the chasm side is

dead.

Repeated

evidence has proved that it can live

on what can not revive

its youth. The sea grows old in it.

“The Fish” by Marianne Moore (1921)

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Marianne Moore stands near her desk in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where she grew up. She graduated from Bryn Mawr College with a degree in biology and histology. Courtesy of the Rosenbach Museum & Library.

M. Sanjayan, CEO of Conservation International, reflects on the playfulness of the “ink- / bespattered jellyfish” in Moore’s poem: “I can't help but smile when I think about that, because it's almost like it's a child's drawing. And that's exactly what you see when you see those jellyfish in the water. It looks like a kid just started doing that with paint.” Courtesy of the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

“For me, the experience of reading this poem was conditioned by the way I, and so many others, see the ocean now as being damaged very severely, unthinkably.” Al Gore brings Marianne Moore’s poem “The Fish” into dialogue with the climate crisis and the destructive effects of changing global temperatures—one example among many—on our oceans.

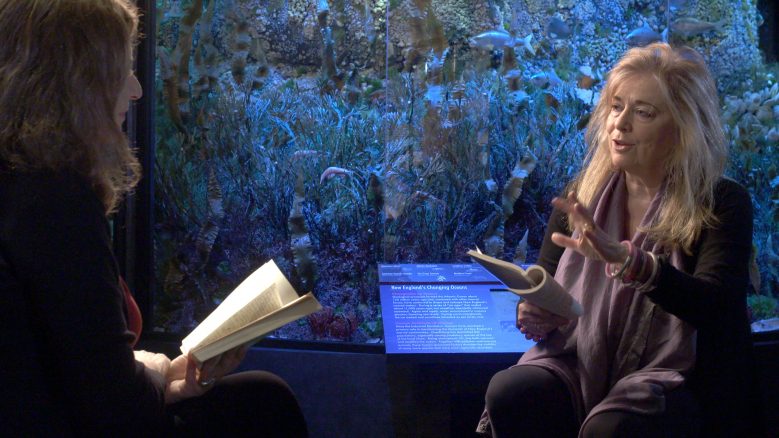

“I think it's important to remember that this poem is in a book called OBSERVATIONS, and the idea of observing is a very different idea than looking, or thinking.” Contemporary poet and Pulitzer Prize-winner Jorie Graham considers the effect that Marianne Moore’s poem “The Fish” has on its reader: “She's trying to get you to both observe, but also to undergo the practice of observing so that you can be transformed.”